Roger Dunham

Updated November 18, 2025

7 min

Extracting Attached Images from a PDF

Roger Dunham

Summary: Developers can use the Apryse SDK to extract not just inline images but also embedded or attached image files from PDFs converted from .MSG emails. This approach is ideal for automating workflows like collecting user-submitted media, archiving attachments for eDiscovery, or processing visual data for ML training using simple, cross-language SDK methods in C#, Java, Python, or Node.js.

Introduction

In a previous article, we looked at how you can use the Apryse SDK to convert a .MSG file into a PDF, then extract the images that are in the body of the document.

That’s a really powerful step. But it doesn’t deal with images that are embedded as files in the PDF, or which are attached via an attachment annotation.

Embedded images are common when working with emails. In fact, if you drag an image into the email, it may well be automatically attached, and when converted to a PDF, it becomes an attached file, and we may still wish to extract embedded images.

Unfortunately, that means that it is not part of the message body and therefore won’t be found by looking at the elements that make up the PDF, which was the process used in the previous article to extract the images.

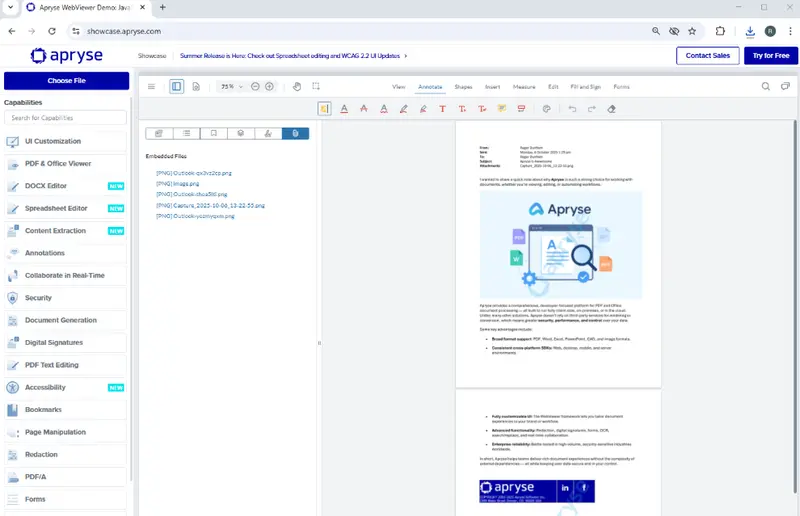

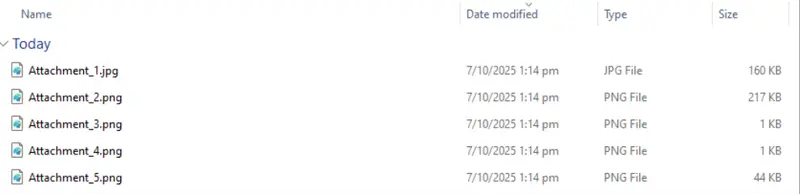

If we open the converted PDF in a quality PDF viewer such as within the Apryse WebViewer Showcase, then we can see those Embedded files.

Figure 1: Files embedded within a PDF, shown in WebViewer running in the Apryse Showcase.

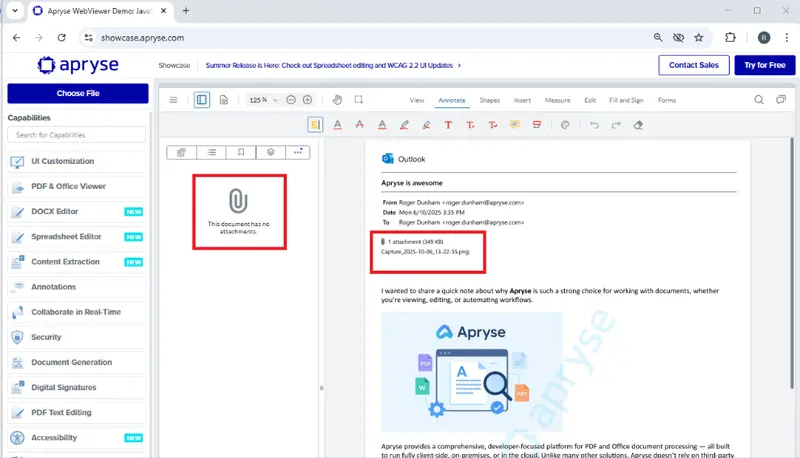

While that is a little awkward, it’s still a much better result that would have been achieved if we had just converted the email into a PDF using the Adobe print driver in Outlook. If we do that, then the generated PDF shows that there was an attachment, but the actual file has been discarded.

Figure 2: Converting the Email into a PDF using the Adobe Print driver in Outlook results in attached files being lost.

Clearly, conversion with Apryse is the superior choice, and even though the attached image isn’t in the body text, it can still be extracted using the Apryse SDK.

In this article, we will see how easy that is to do.

The sample code is in C# for .NET Core, but the Apryse SDK is available in many languages, including Java, C++, Python and Node.JS.

Extracting files attached to the PDF

The code is a little complex, since we need to work with some low-level “COS” objects within the PDF. I’ll explain what is going on as we go through the article, and I’ll use the online tool Cosedit.com to help us to look into the inner workings of a PDF.

Let’s look at the code first and then step through each part in turn.

The first step is to create a PDFDoc object. One way to do that is to create one using the path to a PDF. An alternative, which we used in the previous blog, was to create an in-memory PDFDoc object by converting a .MSG file. For now, let’s create it using a path, that way you don’t need to generate the PDF every time you run the code.

PDFDoc doc = new PDFDoc(pathToPDF);Once we have the PDFDoc object, we can use some custom code, that I have called GetTopLevelAttachments passing in the PDFDoc object.

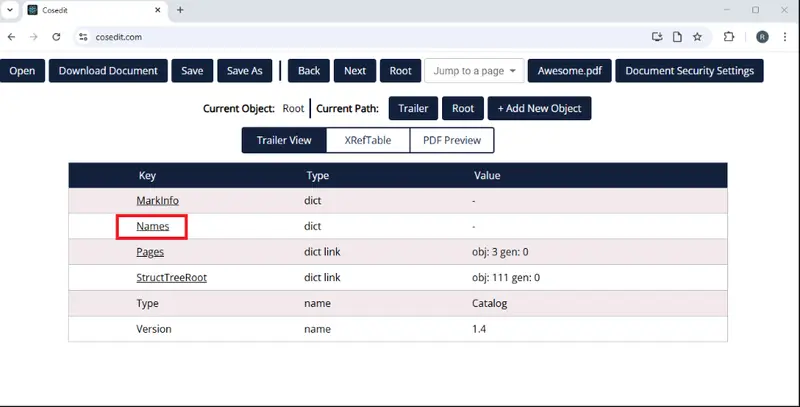

That looks scary, so let’s break it up into more understandable steps. For that, we will need to look at the inner structure of a PDF, and Cosedit is a great tool for doing that.

Step 1: Find the Names object

Within a PDF, attached files are ultimately stored in a Names object, which is a dictionary.

Figure 3: The "Names" object shown in Cosedit.

We’re getting that using:

Obj names = doc.GetRoot().FindObj("Names");Step 2: Get the EmbeddedFiles object

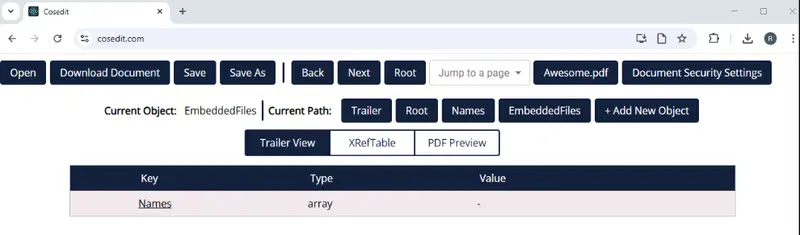

The Names dictionary contains an EmbeddedFiles object if there are attached files.

Figure 4: The "EmbeddedFiles" object within "Names."

We are getting that using:

Obj embeddedFiles = names.FindObj("EmbeddedFiles");Step 3: Creating a NameTree for Embedded objects

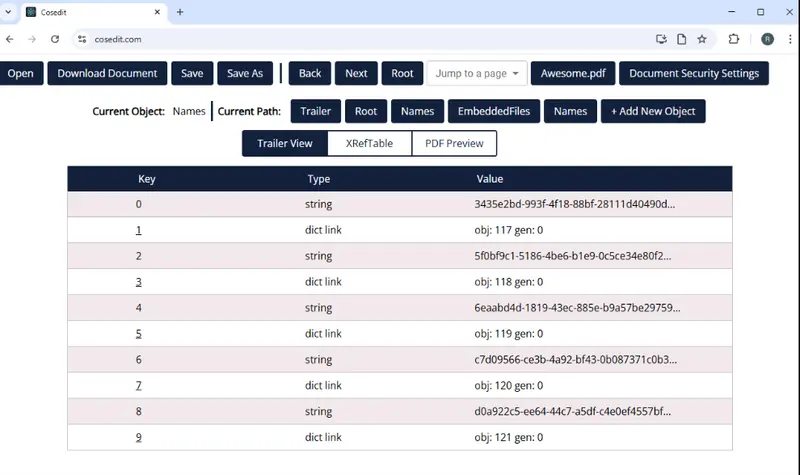

If the EmbeddedFiles object is present, then it will (or at least should) contain a Names array.

Figure 5: The "Names" array within the EmbeddedFiles object.

We can access that by creating a new NameTree object.

NameTree attachments = new NameTree(embeddedFiles);The NameTree is an array of objects that includes links to FileSpec objects that contain the information for each of the embedded files.

Figure 6: The objects in the Names array. The “dict link” objects will take us to the FileSpec objects for each attachment.

Step 4: Iterate through each element in the Names array

Next, we need to iterate through each “dict link” element in the array. This gives us the details for a single FileSpec object.

NameTreeIterator iter = attachments.GetIterator();

while (iter.HasCurrent())

{

// Do things with the items

iter.Next();

}

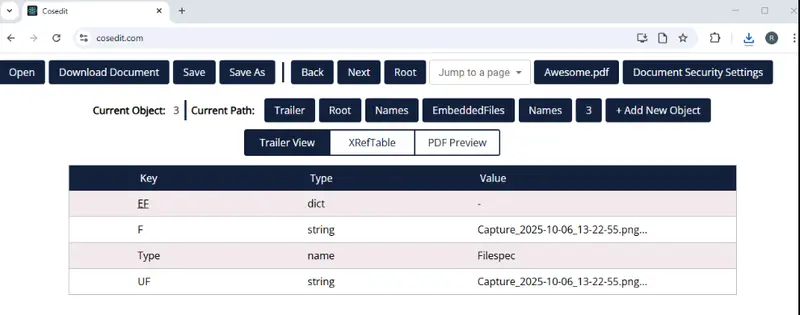

Figure 7: Details for a single FileSpec.

Phew! We have finally arrived at the information about the attached files. The Keys that we are seeing are:

- “EF”: link to the Embedded File

- “F”: The filename

- “UF”: Unicode filename

We can get that FileSpec object using:

Obj fileSpecObj = iter.Value();

FileSpec fileSpec = new FileSpec(fileSpecObj);Step 5: Do something with the FileSpec object

We are now at a point where we can get a stream containing the file (using filespec.GetFileData()) and the name of the file using fileSpec.GetFilePath().

It seems like we have all that we need.

Saving the file

We could save the file stream right now (assuming that it is not null), but it’s wise to be cautious.

Very often you don’t have complete control over where the PDF (or the email that was used to create the PDF) came from. Maybe it originated from someone who is trying to hack your company. For all we know the PDF could contain arbitrary, and potentially malicious, files.

Blindly downloading all the attached files could provide a vector for getting malware onto the server.

For example, it might be extremely unwise to download a python script or an executable file that was in a PDF. If you have complete control over what is in the PDFs then that might be perfectly acceptable of course, but that is a decision that you need to make.

For now, let’s create a new method that takes the FileSpec object, gets the file extension and verifies that the file extension is one that is included in a “whitelist.” In my case, I’m just allowing JPEGs, PNG and GIF files.

If the file extension is OK, we will save it. This is still rather naïve though as it assumes that the file extension has not been tampered with. You might, therefore, want to perform more checks on the file, perhaps verifying that the content matches the file extension, but for simplicity, I’ll not do that here.

For the sake of this article, I am also providing a prefix which will be used when creating filenames, and I’m counting the number of attachments, so that I can use that to discriminate between different files. You may choose to do something different.

The process of saving the file involves taking the stream that was read from the FileSpec object, and writing it, in blocks, into an output stream.

If we run the code, then after a few moments, new files appear in the output folder, one for each of the attached image files in the PDF.

Figure 8: The embedded files extracted to the output folder.

We are now free to do whatever we want with those files – archive them, use them as input for a Small Language Model, or whatever else your workflow requires.

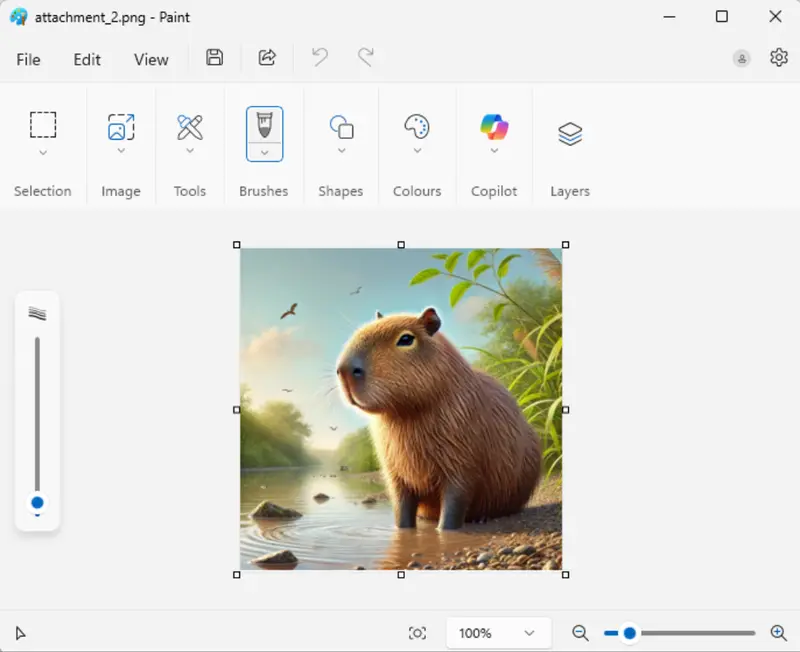

For now, we will just open one of the files to see its contents. For the example PDF, I know that the second file is the image of a capybara that had been attached to the original email.

Figure 9: The image that was attached to the original email message.

Cool, we have proof that we managed to extract an image that had been attached to an email message.

In the previous article, we converted a .MSG file into a PDF using the Apryse SDK to control Outlook. One of the quirks of the process is that if images were present in the body of the message, then they end up being both shown in the body of the PDF and included as embedded files.

When the images are extracted, the image size may differ depending on whether it was in message body or attached. That’s because extracting the images as elements results in them being saved as the size that they are within the PDF, whereas saving as attachments gets them as the actual unscaled size of the image.

Extracting images from attachment annotations

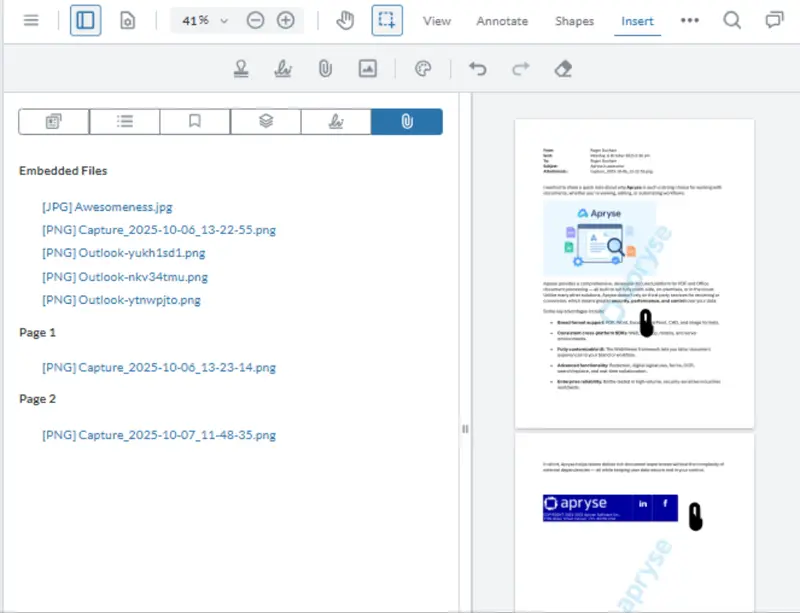

While we are looking at attachments, let’s take the sample PDF and add a couple of attachment annotations. Attachment annotations differ from Embedded files since they are associated with a specific page, and their location in the document is shown by a graphic (for example a paperclip).

Figure 10: Our sample PDF now has two attachment annotations.

If we try our existing code with that PDF, then we won’t find those attachments, because up until now we only looked at embedded files and haven’t been interested in annotations.

Fortunately, it is easy to add a new method to find them.

The code searches through all of the annotations on a specific page and checks whether each one has a “FileAttachment” subtype.

When it finds one, the code gets the FileSpec object, in a similar, but slightly different, way to how we processed embedded files.

From that point onwards, the verification, and saving, of the file is the same as before.

The code needs to work through each page in turn (since annotations are associated with a specific page). We can do that with code such as:

We already have a function very similar to that in the previous article, so all that is really needed is to add the line FindAttachments(page, pageNumber);.

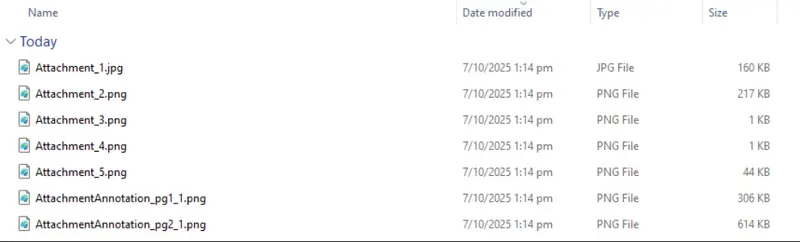

Now when we run the code, images are extracted whether they were in embedded files or attachment annotations.

Figure 11: Now we can get attachments whether they are embedded or attached in annotations.

Wrapping up

This article has been a deep dive into the inner working of the PDF file structure. You’ve seen though how with just a few lines of code we have control over low-level COS objects. You can extend the code further, of course. You might want to download things other than images. Or you might want to work with other annotations. In either case, the sample code used in this article which is available on GitHub is a good place to start.

There are also dozens of other samples that either ship with the Apryse SDK, or you can download directly from the Apryse Documentation.

There’s nothing like trying things out for yourself though, so download the SDK, get a trial license, and have a go. If you have any questions, then you reach out to us on our support channel.